Here’s something most people don’t think about until their generator starts underperforming: power factor. I know, I know—it sounds like one of those technical terms that belongs in an engineering textbook, not a conversation you’d have over coffee. But stick with me here, because understanding Power Factor on Generators might just save you thousands of dollars and a whole lot of headaches.

Think of power factor as your generator’s efficiency rating—except it’s measuring something far more nuanced than just fuel consumption. It’s the secret handshake between the power your generator produces and the power your equipment actually uses. And if you’re running a business, managing a facility, or even just relying on backup power, this invisible metric is quietly affecting your bottom line.

Let me tell you why this matters more than you think.

What Exactly Is Power Factor on a Generator (And Why Should You Care)?

Let’s start with the basics. Power factor is essentially a measure of how effectively your electrical equipment uses the power your generator supplies. It’s expressed as a number between 0 and 1 (or as a percentage), where 1.0 represents perfect efficiency.

Here’s where it gets interesting: not all the power your generator produces actually does useful work. Some of it—called reactive power—just bounces back and forth between your generator and inductive loads like motors, transformers, and compressors. It’s like having someone on your team who looks busy but isn’t actually accomplishing anything.

The power your equipment uses to do actual work is called real power (measured in kilowatts or kW). But your generator has to supply both real power and reactive power, which together create apparent power (measured in kilovolt-amperes or kVA). The power factor is the ratio between these two.

Think of it this way: you’re throwing a dinner party. The real power is your actual guests—the people who show up, eat, and make the evening worthwhile. Reactive power? That’s the extra chairs, plates, and food you prepared for the people who said “maybe” but never confirmed. You still had to prepare for them, even though they didn’t contribute to the actual party.

The Real-World Impact

When yourPower Factor on Generators drops below optimal levels, your generator has to work harder to deliver the same amount of useful power. This means:

- Increased fuel consumption (your wallet feels this one immediately)

- Higher operating temperatures (accelerated wear and tear)

- Reduced effective capacity (you might not be able to run all the equipment you thought you could)

- Potential voltage drops (hello, flickering lights and equipment malfunctions)

I’ve seen facility managers scratch their heads wondering why their brand-new generator can’t handle the load it was supposedly rated for. Nine times out of ten? Power factor issues.

How Power Factor Is Calculated for Generators: The Math Made Simple

Okay, I promised to keep this accessible, so let’s demystify the calculation without turning this into a physics lecture.

The formula is beautifully straightforward:

Power Factor = Real Power (kW) / Apparent Power (kVA)

Or, if you prefer the trigonometry angle (pun intended):

Power Factor = cos θ

Where θ (theta) is the phase angle between voltage and current.

Let’s break this down with a real example. Say your generator is rated at 100 kVA with a 0.8 power factor. Here’s what that actually means:

- Apparent Power (what the generator supplies) = 100 kVA

- Real Power (what you can actually use) = 100 kVA × 0.8 = 80 kW

- Reactive Power (the “wasted” component) = approximately 60 kVAR

That’s a 20 kW difference—which, depending on your operation, could mean the difference between having enough power and experiencing brownouts.

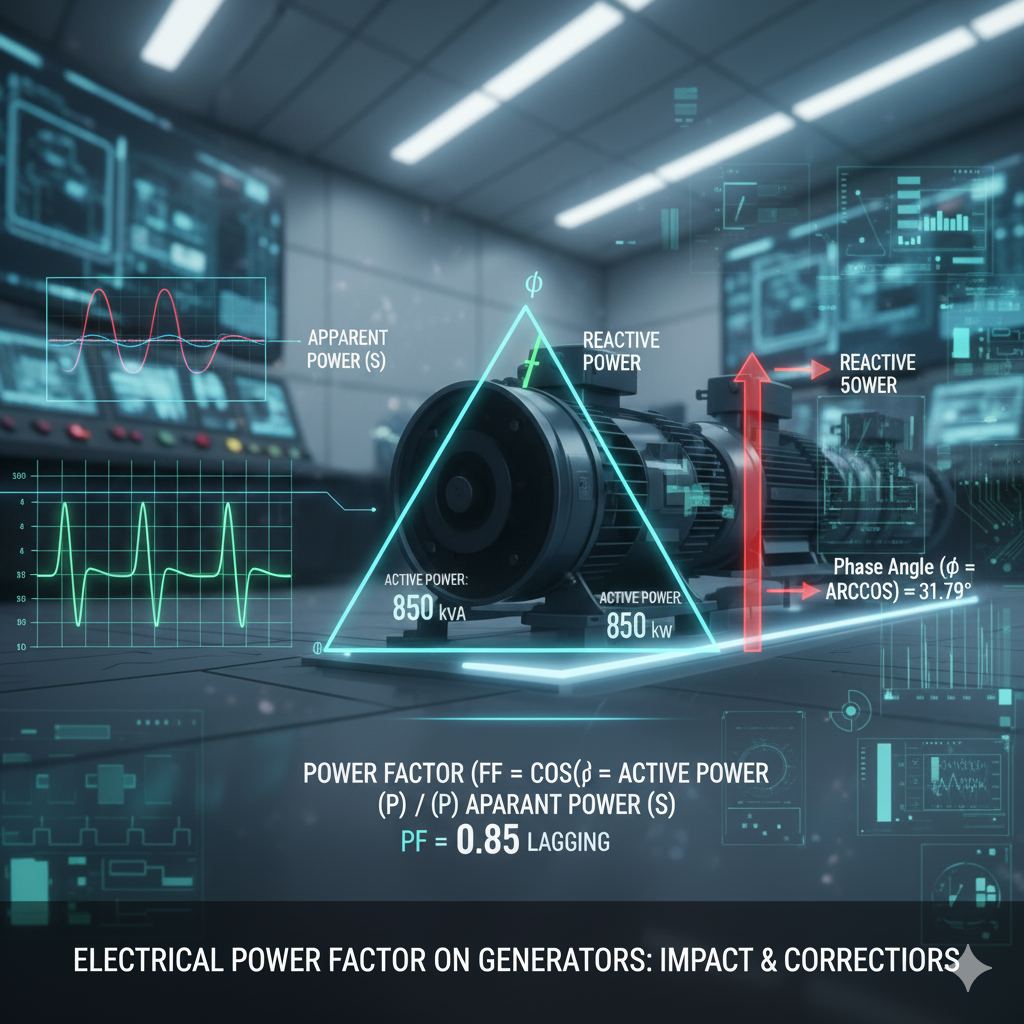

The Triangle That Explains Everything

Electrical engineers love their power triangle, and for good reason. Picture a right triangle where:

- The horizontal leg represents Real Power (kW)—your useful work

- The vertical leg represents Reactive Power (kVAR)—the necessary evil

- The hypotenuse represents Apparent Power (kVA)—what your generator must supply

The angle between real power and apparent power? That’s your power factor angle. The smaller the angle, the closer you are to unity power factor (1.0), which is electrical nirvana.

Why Most Three-Phase Generators Sport a 0.8 Power Factor Rating

Walk into any generator showroom, and you’ll notice something curious: nearly every three-phase generator carries a 0.8 power factor rating. This isn’t arbitrary—it’s a carefully calculated industry standard that reflects real-world electrical loads.

Here’s the thing: most industrial and commercial equipment operates with inductive loads. Motors, transformers, air conditioning systems, welding equipment—they all create lagging power factors (meaning current lags behind voltage). The typical range for these loads? You guessed it: around 0.8.

Manufacturers rate Power Factor on Generators at 0.8 power factor because:

- It matches common load profiles – Most industrial applications naturally operate in this range

- It provides a safety margin – Better to undersize slightly than overcommit

- It’s an international standard – ISO 8528 specifies 0.8 as the reference power factor

- It optimizes cost vs. capability – Building a generator for unity power factor would make it significantly larger and more expensive

Think of it as sizing a restaurant kitchen. You don’t design it for Thanksgiving dinner every single day—you design it for typical service with a little buffer for busy periods.

The Economics Behind the 0.8 Standard

Here’s what fascinates me: if manufacturers built generators for unity power factor (1.0), you’d need about 25% more copper windings and a larger alternator. That means a significantly heavier, more expensive machine. By standardizing at 0.8, manufacturers deliver the power most customers actually need at a price point that makes sense.

But—and this is crucial—if your facility operates with loads that have better power factors (say, 0.9 or higher due to power factor correction), you can actually get more usable power from the same generator. It’s like discovering your car has an extra gear you didn’t know about.

Single-Phase vs. Three-Phase: The Power Factor on Generators Showdown

Now we’re getting into territory where things get really interesting. The difference between single-phase and three-phase generators regarding power factor isn’t just academic—it has profound practical implications.

Single-Phase Generators

Single-phase generators typically serve residential applications and small commercial setups. They generally have:

- Power factors closer to unity (0.95-1.0) for resistive loads like heaters and incandescent lighting

- More variation depending on the specific load mix

- Simpler power factor correction requirements (when needed)

I think of single-phase systems as straightforward—what you see is pretty much what you get. Your typical home loads (refrigerators, HVAC, electronics) create relatively balanced power factors, especially with modern equipment.

Three-Phase Generators

Three-phase systems, conversely, are where power factor becomes critically important:

- Standard 0.8 power factor rating as we discussed

- Better suited for large motors and industrial equipment

- More complex power factor considerations due to load balancing across phases

- Greater efficiency in power transmission and utilization

Here’s a comparison that illustrates the practical differences:

AspectSingle-PhaseThree-PhaseTypical ApplicationsHomes, small offices, light commercialIndustrial facilities, large commercial buildingsCommon Power Factor0.95-1.00.8-0.9Load CharacteristicsMostly resistiveHeavy inductive (motors, compressors)Power DeliveryPulsating, less consistentSmooth, continuousEfficiencyLower for large loadsHigher for equivalent loadsPower Factor Correction NeedsOccasionalFrequently beneficial

The three-phase advantage becomes undeniable when you’re running multiple large motors or heavy equipment. The power delivery is smoother, more efficient, and—when properly managed—more economical.

How Low Power Factor on Generators Hijacks Your Generator Capacity

This is where power factor stops being theoretical and starts costing you real money. Low power factor is like a thief that steals your generator’s capacity without you even realizing it’s happening.

Let’s say you’ve got a 200 kVA generator rated at 0.8 power factor. Under ideal conditions, that gives you 160 kW of usable power (200 kVA × 0.8 = 160 kW). Sweet, right?

But now imagine your facility’s actual Power Factor on Generatorsr drops to 0.6 due to inefficient equipment or poor load management. Suddenly, your effective capacity plummets. Here’s the brutal math:

At 0.6 power factor, that same 200 kVA generator only delivers:

- 120 kW of usable power (200 kVA × 0.6)

- That’s a 25% reduction in effective capacity

- You’ve essentially “lost” 40 kW without anything physically breaking

The Domino Effect

When power factor drops, several things happen simultaneously—and none of them are good:

Increased Current Draw: To deliver the same amount of real power, the generator must supply more current. This means:

- Higher I²R losses (current squared times resistance) in the windings

- Increased heat generation

- Faster insulation degradation

- Shortened equipment lifespan

Voltage Regulation Issues: Excessive reactive power causes voltage drops across the system, leading to:

- Dimming lights

- Motor performance issues

- Potential equipment damage

- Nuisance tripping of protective devices

Reduced Load Capacity: Your generator simply can’t power as many devices as its nameplate suggests, forcing you to either:

- Invest in a larger (more expensive) generator

- Implement power factor correction

- Reduce your operational capacity

I once consulted for a manufacturing facility that was convinced they needed to upgrade from a 500 kVA to a 750 kVA generator. Their power factor? A dismal 0.65. After installing power factor correction capacitors (total cost: about $15,000), their existing generator handled the load beautifully. They saved over $80,000 by understanding this one principle.

What Happens When Load Power Factor on Generators Falls Below Generator Rating?

Here’s a scenario that happens more often than you’d think: your generator is rated at 0.8 power factor, but your actual load operates at 0.6 or 0.7. What now?

Short answer: Your generator doesn’t explode, but it does get seriously cranky.

The generator will continue operating, but several problems emerge:

Overheating and Stress

The alternator must produce additional current to compensate for the poor Power Factor on Generators. This creates:

- Excess heat in the stator windings

- Increased thermal cycling (expansion and contraction)

- Accelerated aging of insulation materials

- Potential for premature failure

Think of it like constantly redlining your car’s engine. Sure, it’ll run for a while, but you’re shaving years off its life expectancy.

Voltage Instability

Poor Power Factor on Generators creates larger voltage drops throughout the system. You might notice:

- Lights dimming when motors start

- Equipment running sluggishly

- Unexplained shutdowns or resets

- Difficulty starting large loads

Protection System Activation

Modern generators have sophisticated protection systems. When power factor drops too low:

- Overcurrent protection may trip unnecessarily

- Voltage regulators struggle to maintain setpoints

- Frequency stability may suffer under varying loads

- The generator might derate itself automatically to prevent damage

The Hidden Cost

Here’s what really gets me: poor Power Factor on Generators forces you to pay for capacity you’re not using. If you’re running at 0.6 power factor instead of 0.8, you need a generator that’s 33% larger than what you’d otherwise require. That’s 33% more in:

- Initial capital costs

- Fuel consumption

- Maintenance expenses

- Physical footprint

It’s like buying a 10-bedroom mansion when you only need a 3-bedroom house—and then paying to heat, cool, and maintain all those empty rooms.

Power Factor on Generators Correction: Your Secret Weapon

Alright, enough doom and gloom. Let’s talk solutions. Power factor correction is one of those rare scenarios where you can actually improve performance and save money simultaneously.

Capacitor Banks: The Classic Approach

Capacitors are the workhorse of power factor correction. They supply reactive power locally, reducing the burden on your generator. Here’s why they work:

Inductive loads (motors, transformers) create lagging current—current that follows voltage. Capacitors do the opposite, creating leading current that arrives before voltage. When properly sized, they cancel each other out, bringing your power factor closer to unity.

Types of Capacitor Banks:

- Fixed Capacitor Banks

- Permanently connected to the system

- Simple, reliable, cost-effective

- Best for steady, predictable loads

- Typical cost: $50-$200 per kVAR

- Automatic Power Factor Controllers

- Dynamically adjust capacitance based on load

- Respond to changing conditions in real-time

- Prevent over-correction (which creates its own problems)

- Higher initial cost but optimal performance

Static Var Generators (SVGs): The Premium Solution

For operations requiring precise, fast-responding power factor correction, SVGs represent the cutting edge. These sophisticated devices:

- React in milliseconds (vs. seconds for mechanical contactors)

- Provide continuous adjustment

- Handle harmonics better than traditional capacitors

- Cost significantly more but deliver superior performance

I’ve seen SVGs transform problematic installations into smooth, efficient operations. They’re particularly valuable in facilities with highly variable loads or sensitive equipment.

Synchronous Condensers: Old School Cool

Before solid-state electronics, synchronous condensers (essentially unloaded synchronous motors) handled power factor correction. They’re less common now but still valuable in specific applications requiring:

- Large amounts of reactive power

- Excellent voltage support

- Mechanical inertia for grid stability

Practical Correction Strategies

Step 1: Measure Your Actual Power Factor You can’t improve what you don’t measure. Install power factor meters or use a quality power analyzer (like the Fluke 435) to establish your baseline.

Step 2: Calculate Required Correction Determine the kVAR of capacitance needed to reach your target power factor (usually 0.95 or higher). Online calculators and software tools make this straightforward.

Step 3: Select Appropriate Equipment Choose between fixed, automatic, or advanced solutions based on:

- Load variability

- Budget constraints

- Available space

- Maintenance capabilities

Step 4: Install and Commission Professional installation is crucial. Incorrectly sized or installed capacitors can create resonance issues, voltage spikes, or equipment damage.

Step 5: Monitor and Adjust Power factor isn’t set-and-forget. As your load profile changes, reassess and adjust your correction strategy.

Real-World Correction Example

A data center I worked with had a 1000 kVA generator operating at 0.72 power factor. Their usable power: 720 kW. After installing 300 kVAR of automatic power factor correction (cost: approximately $25,000), they improved to 0.93 power factor, yielding 930 kW—a 29% increase in usable capacity without upgrading the generator. ROI? Less than two years.

Applications That Murder Your Power Factor on Generators

Not all loads are created equal when it comes to power factor. Some are particularly notorious for dragging it down. Let’s name names.

The Usual Suspects

1. Electric Motors The biggest culprits in most facilities. Large motors, especially when lightly loaded, can operate at power factors as low as 0.6. Induction motors are inherently inductive, requiring magnetizing current that contributes nothing to shaft power.

Pro tip: Motors operating below 50% of rated load are power factor disasters. Right-sizing motors for their actual load makes a huge difference.

2. Welding Equipment Arc welders are notoriously terrible for power factor—often 0.5 to 0.7. The arcing process creates highly reactive loads with significant harmonics thrown in for good measure.

3. Transformers Even unloaded transformers consume reactive power for magnetization. Older, oversized transformers are particularly bad. If you’ve got 1970s-era transformers still in service, they’re probably costing you more than you realize.

4. Discharge Lighting Older fluorescent, metal halide, and high-pressure sodium fixtures without power factor correction ballasts can operate at 0.5-0.6 power factor. LED upgrades improve power factor while slashing energy consumption—a win-win.

5. HVAC Systems Large commercial HVAC systems with multiple compressors and fan motors create substantial reactive loads. Variable frequency drives (VFDs) can help, but they introduce harmonics that require additional consideration.

6. Elevators and Hoists The large motors and regenerative braking systems in elevator systems create complex load profiles with poor power factor during acceleration and deceleration.

The Modern Wildcards

Here’s where things get interesting with contemporary technology:

Data Centers and IT Equipment Modern switched-mode power supplies actually have decent power factors (0.9-0.95) when properly designed. However, the sheer concentration of this equipment can still stress generators, and harmonic distortion becomes the bigger concern.

Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs) VFDs improve motor efficiency and allow for speed control, but they’re a double-edged sword for power factor. While they can improve the motor’s effective power factor, they introduce harmonics that distort the current waveform, potentially fooling power factor measurements and causing other issues.

Battery Charging Systems Large battery banks in UPS systems, electric vehicle charging stations, and telecommunications facilities draw nonlinear currents that complicate power factor management.

The Power Factor on Generators-Fuel Consumption Connection

Let’s talk about something that hits every balance sheet: fuel costs. Poor power factor doesn’t just reduce capacity—it actively burns through diesel (or natural gas, or propane) at an alarming rate.

Here’s the mechanism: when power factor drops, the generator must supply more current to deliver the same real power. More current means more I²R losses in the windings and conductors. Those losses manifest as heat—heat that came from combusted fuel.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

Consider a 500 kW load at two different power factors:

Scenario A: 0.95 Power Factor

- Apparent Power Required: 526 kVA

- Generator Loading: Moderate

- Current Draw: Optimal

- Estimated Fuel Consumption: 100% (baseline)

Scenario B: 0.70 Power Factor

- Apparent Power Required: 714 kVA

- Generator Loading: Heavy

- Current Draw: 36% higher

- Estimated Fuel Consumption: 108-112%

That 8-12% increase in fuel consumption adds up fast. For a generator running 2,000 hours annually at $3.50/gallon for diesel, consuming 15 gallons per hour at baseline:

- Annual fuel cost at 0.95 PF: $105,000

- Annual fuel cost at 0.70 PF: $115,500

- Additional cost: $10,500 per year

Over a 10-year equipment lifecycle, that’s $105,000 in unnecessary fuel expenses—enough to pay for comprehensive power factor correction several times over.

Beyond Fuel: The Efficiency Ripple Effect

The efficiency impact extends beyond direct fuel consumption:

- Increased maintenance intervals due to higher operating temperatures

- Shortened engine and alternator life from sustained heavy loading

- More frequent oil changes (oil degrades faster at higher temperatures)

- Cooling system stress requiring more attention and eventual replacement

- Exhaust system degradation from sustained high temperatures

I’ve seen generators that should last 20,000 hours fail at 12,000 hours because of chronic poor power factor operation. That’s replacing a major asset 40% earlier than planned—a catastrophic unplanned expense.

Can Power Factor Exceed 1.0? The Unity Paradox

Here’s a question that comes up surprisingly often: can power factor be greater than 1.0?

The theoretical answer: No. Power factor is defined as the ratio of real power to apparent power. Since apparent power is the vector sum of real and reactive power, it must always be equal to or greater than real power. Therefore, power factor maxes out at 1.0 (unity power factor).

The practical answer: Kind of, but not really—and when it appears to, you’ve got problems.

When Power Factor “Exceeds” Unity

If your instruments show a power factor above 1.0, one of several things is happening:

1. Leading Power Factor Over-correction with capacitors can create a leading power factor (current leads voltage instead of lagging). This is still technically less than 1.0, but it’s measured and displayed as a leading value (e.g., “0.92 leading” instead of “0.92 lagging”).

Leading power factors create their own issues:

- Voltage rise on the system

- Potential damage to equipment

- Resonance with system inductance

- Inefficient operation

2. Measurement Error Cheap or miscalibrated instruments might display impossible values. Quality power analyzers don’t make this mistake, but basic meters might.

3. Harmonic Distortion Severe harmonic distortion can confuse measurement algorithms that assume pure sinusoidal waveforms. The “power factor” reading becomes meaningless without also measuring harmonic content.

Unity Power Factor: The Goal

Striving for unity power factor (1.0) seems logical, but in practice, slightly lagging (0.95-0.98) is actually ideal for most generator systems:

- Provides safety margin against over-correction

- Avoids leading power factor complications

- Optimizes efficiency without excessive correction equipment

- Maintains system stability

Think of it like driving: technically, you could try to maintain exactly 65.000 mph on the highway, but constantly adjusting to maintain that precision would be exhausting and counterproductive. Similarly, 0.95-0.98 power factor gives you excellent performance without obsessive fine-tuning.

Reactive Power, Apparent Power, and the Generator Triangle

We touched on this earlier, but let’s dive deeper into the relationship between reactive power, apparent power, and how they impact generator operation.

The Three Types of Power

Real Power (P) – Measured in Kilowatts (kW) This is the power that does actual work—running motors, lighting facilities, computing data. It’s what you’re really paying for and what makes your operation function.

Reactive Power (Q) – Measured in Kilovolt-Amperes Reactive (kVAR) This is the power that shuttles back and forth, magnetizing motor windings and transformer cores. It’s necessary for the operation of inductive equipment but does no useful work. Think of it as the “organizational overhead” of electrical systems.

Apparent Power (S) – Measured in Kilovolt-Amperes (kVA) This is the total power your generator must supply—the vector sum of real and reactive power. It represents the total capacity your generator needs, regardless of how efficiently it’s being used.

The Mathematical Relationship

These three powers form a right triangle (the power triangle):

- S² = P² + Q² (Pythagorean theorem in electrical form)

- Power Factor = P / S = cos θ

Where θ is the phase angle between voltage and current.

Why Generators Are Rated in kVA, Not kW

Here’s something that confuses people: why do generators carry kVA ratings instead of kW ratings?

Simple: kVA represents the generator’s physical capability, independent of the load’s power factor. The alternator’s copper windings, magnetic fields, and thermal limits are stressed by total current (apparent power), not just the useful component.

A 100 kVA generator can supply:

- 100 kW at unity power factor (1.0)

- 80 kW at 0.8 power factor

- 60 kW at 0.6 power factor

The generator doesn’t care what you do with the power—it’s limited by how much current flows through its windings. That’s kVA, not kW.

Practical Implications for Generator Sizing

When sizing a generator, you must account for both real and reactive power demands:

Step 1: Calculate total real power requirements (sum all kW loads) Step 2: Determine the expected power factor of your combined loads Step 3: Calculate required apparent power: kVA = kW / Power Factor Step 4: Add safety margin (typically 20-25%) Step 5: Select the next larger standard generator size

Example:

- Total load: 400 kW

- Expected power factor: 0.8

- Required kVA: 400 kW / 0.8 = 500 kVA

- With 25% margin: 625 kVA

- Selected generator: 650 kVA (next standard size)

If you sized based on kW alone and ignored power factor, you’d end up with an undersized generator that can’t handle your actual load. This mistake costs businesses thousands—or even millions—every year.

Generator Sizing for Industrial Applications: The Power Factor Imperative

Industrial generator sizing is where power factor considerations become absolutely critical. Get it wrong, and you’re either wasting capital on oversized equipment or experiencing chronic capacity issues with undersized units.

The Industrial Reality

Industrial facilities typically feature:

- Heavy inductive loads (motors, transformers, welders)

- Dynamic, varying load profiles

- Critical processes that can’t tolerate power interruptions

- Multiple large motors starting simultaneously

- Complex power distribution systems

All of these factors demand careful attention to power factor in the sizing process.

The Comprehensive Sizing Approach

1. Detailed Load Analysis Don’t just sum up nameplate ratings. Understand:

- Actual running loads (often 50-70% of nameplate)

- Motor starting currents (can be 6-8× running current)

- Load diversity (not everything runs simultaneously)

- Future expansion needs

2. Power Factor Assessment Measure or estimate power factor for each major load category:

- Motors: 0.7-0.85 (depending on loading and size)

- Lighting: 0.9-0.95 (modern fixtures) to 0.5-0.6 (older discharge lighting)

- HVAC: 0.75-0.85

- Process equipment: Varies widely—measure if possible

3. Simultaneous Load Calculation Determine which loads operate concurrently. Use a load profile table:

Time PeriodLoad A (kW)Load B (kW)Load C (kW)Total (kW)Combined PFRequired kVADay Shift250180955250.82640Night Shift120180403400.79430Startup3002001156150.75820

4. Starting Current Considerations Large motor starts can momentarily demand 6-8 times running current. Your generator must handle this without excessive voltage dip. Options include:

- Soft starters or VFDs to reduce starting current

- Oversizing the generator

- Sequential start sequences

- Dedicated starting generators for large motors

5. Future Growth Industrial facilities evolve. Build in 25-30% excess capacity for future expansion. It’s far cheaper than replacing an undersized generator three years after installation.

Real-World Industrial Sizing Example

Facility: Mid-size manufacturing plant Primary Loads:

- Three 75 HP motors (continuous): 165 kW

- Process equipment: 85 kW

- HVAC: 45 kW

- Lighting and miscellaneous: 30 kW

- Total continuous load: 325 kW

Additional Factors:

- Facility power factor: 0.78 (measured)

- Largest motor starting: 75 HP (inrush consideration)

- Planned expansion: +100 kW within 3 years

Sizing Calculation:

- Continuous load in kVA: 325 kW / 0.78 = 417 kVA

- Motor starting capacity: Additional 200 kVA transient

- Peak requirement: 617 kVA

- Future growth: +128 kVA (100 kW / 0.78)

- Total projected: 745 kVA

- With 20% margin: 894 kVA

- Selected generator: 1000 kVA (next standard size)

Had they sized based on kW alone (325 kW + 100 kW future = 425 kW), they might have selected a 500 kW / 625 kVA generator—woefully inadequate for their actual needs.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

Undersizing consequences:

- Chronic voltage sags and dips

- Equipment nuisance trips

- Inability to start large motors

- Production downtime

- Premature generator failure from sustained overload

- Emergency replacement costs ($$$$)

Oversizing consequences:

- Higher capital costs (less severe, but still significant)

- Reduced fuel efficiency (engines prefer 70-80% loading)

- More space requirements

- Higher maintenance costs

The sweet spot: properly sized with power factor fully accounted for and reasonable growth margin built in.

How Power Factor Is Measured on Generators

You can’t manage what you don’t measure, and power factor is no exception. Let’s talk about measurement methods, from simple to sophisticated.

Basic Power Factor Meters

Entry-level power factor meters provide real-time display of:

- Power factor (displayed as decimal or percentage)

- Leading or lagging indication

- Sometimes basic kW, kVA, and kVAR readings

These are fine for spot checks but lack data logging and detailed analysis capabilities. Cost: $50-$300.

Best for: Small facilities with stable loads where periodic checks suffice.

Digital Power Factor Meters with Data Logging

Mid-range digital meters add:

- Time-stamped data logging

- Min/max/average recording

- Multiple measurement points

- Communication capabilities (Modbus, Ethernet)

- Integration with building management systems

Cost: $300-$1,500.

Best for: Facilities wanting historical trends and remote monitoring.

Power Quality Analyzers

Professional-grade analyzers (like the Fluke 435 mentioned in your product list) provide comprehensive analysis:

- Power factor measurement with 0.01 resolution

- Harmonic analysis up to 50th harmonic

- Voltage and current waveform capture

- Transient recording

- Flicker and imbalance measurement

- Detailed reporting and analysis software

Cost: $3,000-$8,000.

Best for: Troubleshooting complex power quality issues, commissioning new installations, and detailed system analysis.

Generator-Integrated Monitoring

Modern generator control panels often include built-in power factor measurement:

- Real-time display on controller screen

- Integration with generator protection systems

- Historical data logging

- Remote monitoring capabilities

- Alarm functions for out-of-range conditions

This integrated approach is ideal because it’s always monitoring, doesn’t require separate equipment, and can trigger protective actions if power factor drops too low.

Measurement Best Practices

Location Matters Measure power factor as close to the generator output as practical. This gives you the true picture of what the generator is experiencing, not just individual load circuits.

Duration Matters Single snapshot measurements can be misleading. Log data over representative periods:

- Full production shifts

- Startup and shutdown sequences

- Weekend/off-hours operation

- Seasonal variations (HVAC loads)

Context Matters Power factor alone doesn’t tell the whole story. Also monitor:

- Voltage levels and balance

- Current levels and balance

- Total harmonic distortion

- Frequency stability

Calibration Matters Ensure measurement equipment is properly calibrated. An incorrect power factor reading is worse than no reading at all—it leads to misguided correction efforts.

Interpreting the Results

Power Factor > 0.95: Excellent. System is operating efficiently with minimal reactive power waste.

Power Factor 0.85-0.95: Good. Typical for well-managed facilities. Some room for improvement but not urgent.

Power Factor 0.75-0.85: Fair. Generator is working harder than necessary. Power factor correction should be considered for economic reasons.

Power Factor < 0.75: Poor. Significant capacity loss and efficiency penalty. Correction is economically justified and should be prioritized.

Leading Power Factor: Red flag. Over-correction with capacitors or unusual load conditions. Investigate immediately to prevent equipment damage.

The Consequences of Ignoring Power Factor

Let me paint a picture of what happens when organizations neglect power factor. I’ve seen this play out more times than I care to count, and it’s never pretty.

The Slow-Motion Disaster

Ignoring power factor is like ignoring the “check engine” light in your car. Nothing explodes immediately, but you’re accelerating toward expensive problems.

Year 1-2: The Silent Period

- Generator operates with reduced efficiency

- Slightly higher fuel consumption (often attributed to other factors)

- Occasional voltage